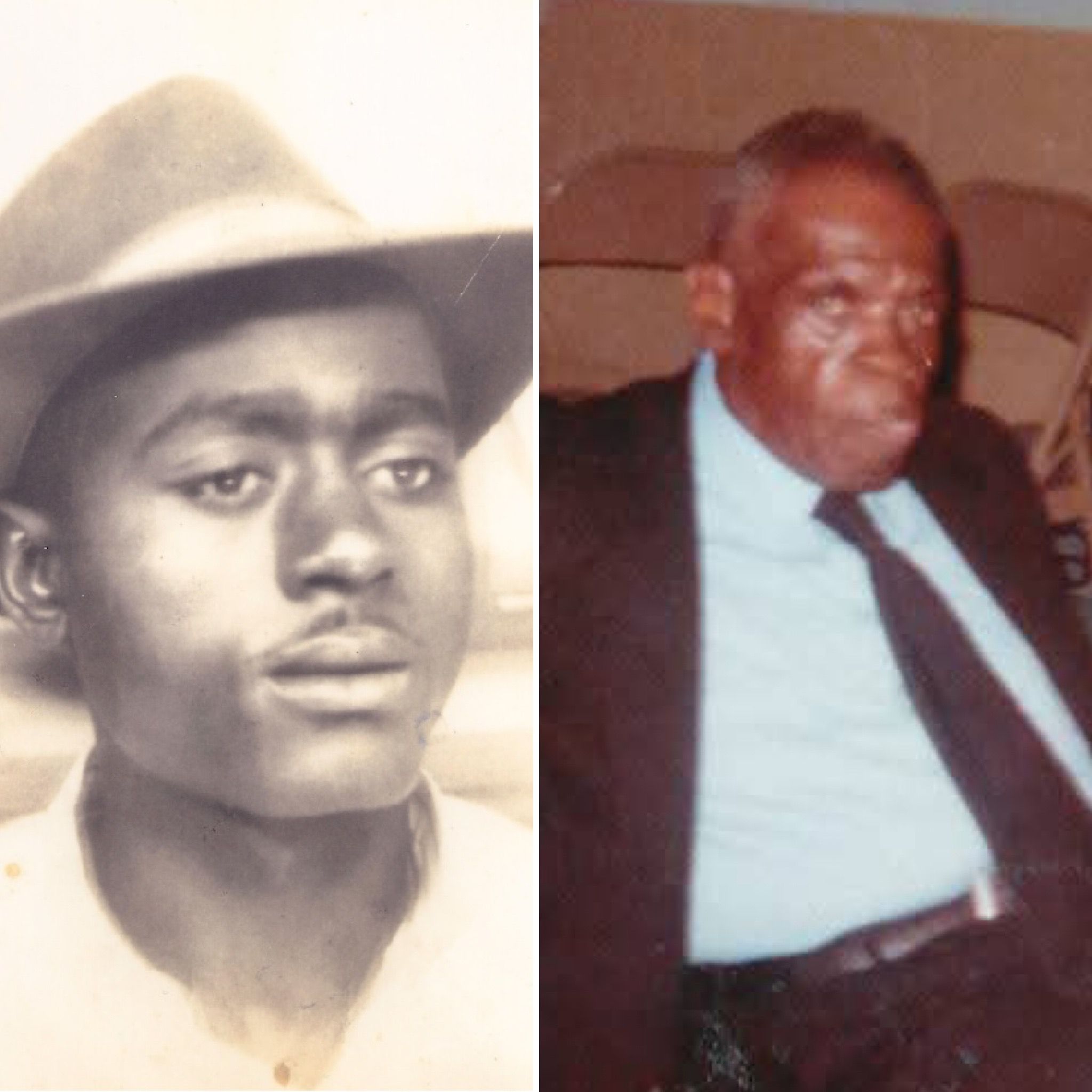

Isaiah Nixon and Dover Carter

Isaiah Nixon was a 28-year-old farmer in Montgomery County, Georgia. He and his wife, Sallie, had six children. Dover Carter was a 42-year-old farmer in Montgomery County, Georgia. He and his wife, Bessie, had 13 children.

Case summary

Incident

In September 1948, Georgia voters participated in a special election to determine the next Democratic candidate for governor: Lieutenant Governor Melvin Thompson or Herman Talmadge, son of the recently deceased governor-elect Eugene Talmadge. The Ku Klux Klan endorsed the younger Talmadge, who, like his father, had made a campaign promise to end Black voting in the state and enforce segregation.

The Klan held a demonstration in Montgomery County, southeast of Macon, on September 4, just days before the election. On election day, September 8, 1948, Montgomery County residents Isaiah Nixon and Dover Carter both cast their ballots.

Nixon and Carter were friends and neighbors, living two and half miles from one another. Nixon, 28, and his wife, Sallie, had six children: Dorothy, Isaiah Jr, Margaret, Connie, Mary, and Hubert. The Nixons lived on a 60-acre farm they owned in Alston, Montgomery County, where they farmed tobacco, cotton, and apples. Nixon’s children remember him taking them to town on a mule-drawn wagon and buying them peppermint candy.

Carter had turned 42 just two days earlier, and he and his wife, Bessie, had 13 children. Carter was a farmer who founded the Montgomery County branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1946 and served as president of the branch in 1948. Carter grew membership of the local NAACP chapter to 100 members. White residents in the area threatened to kill Carter in 1946, when he first started registering Black voters. In 1948, the Montgomery County NAACP registered between 500 and 600 Black people to vote. On Election Day, Carter, at the request of the Thompson campaign, began driving Black registered voters to and from the polls in his truck.

Accounts differed as to what occurred late that morning, as Carter drove an elderly Black woman named Ella Mills home from the polls in Alston. About a mile outside Alston, they passed Mills’s son, Collins, who climbed into the back of the truck. Around the same time, according to Carter’s affidavit, a car with two white men – Johnnie Johnson and Thomas Jefferson Wilson (also known as Thomas Wilkes) – pulled in front of Carter’s truck, forcing him to stop. Johnson and Wilson were brothers-in-law. Johnson got out of the car and demanded that Carter exit his truck, that Johnson intended “to beat the hell out of me,” according to Carter’s affidavit. Meanwhile, Ella Mills and her son got out of the truck and hurried away in the direction of their home. Johnson opened the driver’s side door of Carter’s vehicle and began severely beating Carter with “a piece of iron that was fasten[ed] to his arm,” while Wilson pointed a shotgun at Carter. At one point, according to Carter’s affidavit, Claude Sharpe, the candidate for county sheriff, drove past and he and Johnson shared a laugh. The beating lasted about twenty-five minutes, according to Carter’s account. The men then demanded that Carter go home and not take any more Black voters to or from the polls.

Carter drove home and then went to a white doctor in Ailey, Georgia. The physician, Dr. J. Will Palmer, told the FBI that he treated Carter for severe bruises and lacerations that Palmer believed were “produced by some heavy instruments.”

In their statements to the FBI, both Johnson and Wilson said they had cut off Carter’s truck only after Carter had braked suddenly in front of them. Johnson said that when he approached Carter’s truck, Carter began to reach for a shotgun. Johnson said he grabbed a tire iron from the truck and began beating Carter’s arms and head with it, until Carter dropped the shotgun. Johnson told investigators he beat Carter until he dropped the weapon, which he took and handed to Wilson. Johnson claimed he and Wilson never had any weapons of their own on them. For his part, Sharpe denied to the FBI that he’d ever passed the scene.

That evening, Johnnie Johnson and his brother Jim A. Johnson drove up to the Nixons’ yard in a black car and called for Nixon to come out of the farmhouse. Nixon’s mother, Daisy Davis, was in the house and some of his children were sitting on the porch, and others were picking vegetables in the yard. Sallie Nixon was on bedrest as she was four weeks postpartum. Nixon went out to see the men. Jim and Johnnie got out of the car, Jim with a revolver in his hand and Johnnie with a shotgun. According to one account, Jim asked Nixon for whom he’d voted and Nixon replied, “Guess I voted for Thompson.” Jim ordered Nixon to get in the car but Nixon did not move. Jim fired at Nixon, hitting him twice in the legs and once in the abdomen. Nixon’s daughter, Dorothy, remembers hearing her mother tell her father to “fall, Isaiah, fall” as he stood bleeding in front of the Johnson brothers. Eventually, he collapsed and the Johnson brothers left the property. Sallie Nixon carried her wounded husband into the house.

Aftermath

One of Nixon’s neighbors, A.C. Brown, ran a few miles to the town of Uvalda to find a ride for Nixon and secured a taxi that took Nixon to the closest hospital that would treat Black people – Claxton Hospital in Dublin. Carter visited Nixon in the hospital, and, according to Carter, Nixon told him that the Johnson brothers had shot him after he’d told them he’d voted for Thompson. After leaving the hospital, Carter fled to Atlanta, fearing, he said, for his safety. Nixon died from his bullet wounds on September 10, 1948.

Carter drove to the FBI field office in Atlanta on September 10, 1948, and provided a signed affidavit about his assault and the Nixon shooting. The Atlanta field office sent its report to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and noted that the two incidents “appear to be related and possibly part of an overall conspiracy.” Hoover shared the report with the Department of Justice (DOJ) but did not mention a potential for the federal conspiracy crime, suggesting only that the DOJ might consider the two cases in tandem.

Fearing for their lives, the Nixon family left Georgia under cover of darkness. Sallie Nixon, her six children, and Davis, moved in with relatives in Jacksonville, Florida. All eight of the Nixons shared one bedroom in their relatives’ two-bedroom house. The Pittsburgh Courier reported on the Nixon killing and started a fundraiser to build the Nixons a five-bedroom home in Florida. Sallie Nixon raised her children in their new home and became active in the Parent Teacher Association of their school, the Red Cross, and other community initiatives.

After he left Atlanta, Carter and his family fled to Philadelphia, PA for safety. He started a successful watermelon stand, Carter’s Watermelon, in 1954 and was known in the community as “Deacon Carter the Watermelon Man.” Carter died in Philadelphia on August 16, 1988. He was 81. He and his wife Bessie are buried behind a small church in Dublin, Georgia. The Carter family continues to run his watermelon stand in west Philadelphia.

Montgomery County Sheriff R.M. McCrimmon, who was in his final months in office, arrested the Johnson brothers the week after the shooting and held them in the Mt. Vernon jail without bond – Jim on a murder charge and Johnnie as accessory to murder. By the end of September 1948, the DOJ authorized an FBI investigation into the attacks on Nixon and Carter, but expressed “hesitancy” to investigate “for fear that it might inflame local sentiment.” The FBI chose to move forward with an investigation, in part because of the information Carter provided about Nixon’s death.

Jim and Johnnie Johnson were jointly indicted by a State Grand Jury and charged with Nixon’s murder. Jim went to trial first, on November 4, 1948, and testified that he went to Nixon’s house to offer him a job and shot Nixon only after Nixon advanced on him with a knife. The jury deliberated for two hours before returning a verdict of not guilty. After Jim Johnson was acquitted, the state dropped the case against Johnnie Johnson.

In a December 1, 1948, letter to the DOJ, Thurgood Marshall, chief counsel of the NAACP (and later a Supreme Court justice), requested federal action concerning the Carter and Nixon incidents. In March 1949, the FBI and the DOJ decided to close the Nixon case based on the US Attorney for the Southern District of Georgia’s assessment that further investigation was “not warranted.” In the same month, the DOJ closed the Carter case and wrote Marshall that federal authorities had determined that “the beating of Carter was occasioned by his own act,” based on Johnson and Wilson’s story that Carter had threatened them first.

Case summaries are compiled from information contained in different sources, including, but not limited to, investigative records, arrest reports, court filings, census records, birth and death certificates, transcripts, and press releases. In many cases, the records contain contradictory assertions.