Who we are & what we do

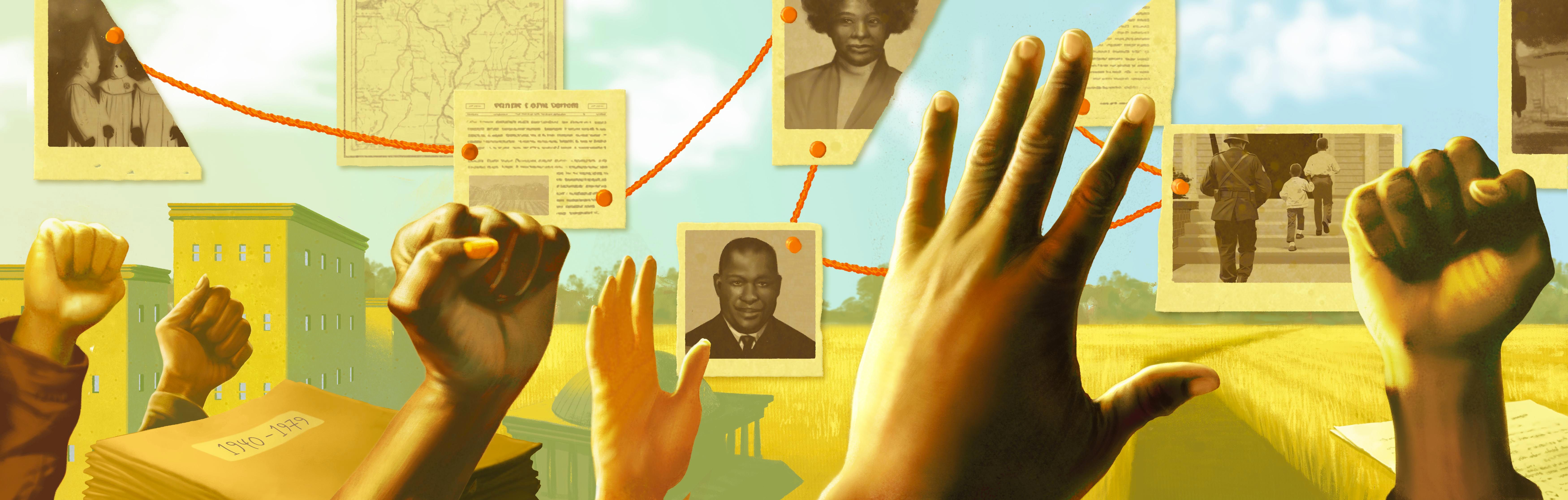

The Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board is a nonpartisan panel of private citizens, appointed by the President, who are working to release the contents of federal investigations into unresolved cold cases from the civil rights era. In making these records publicly available, the goal is to provide a measure of clarity to relatives of victims, and also provide a more comprehensive picture of a dark chapter in our nation’s history. Find out more.

“After all this time, we might not solve every one of these cold cases, but my hope is that our efforts will, at the very least, help us find some long overdue healing and understanding of the truth.”

- Sen. Doug Jones, July 10, 2018, on the floor of the U.S. Senate

Newly released cases

-

Aletha Bell Carter was a 17-year-old high school student from Pine Island, Horry County, South Carolina. The daughter of James Nolon and Archie Bell Carter, she had eight siblings.

Alfonzo Merritt was a 39-year-old coach cleaner in Tuscumbia, Alabama. He was married to Annie Merritt and they had a son, Carl.

Willie Lee Davis was a 24-year-old Army technician from Georgia working in the Detachment Medical Department at New Orleans Army Air Base in New Orleans, Louisiana.

William Fowler was a 23-year-old cook who lived in Spartanburg, South Carolina with his wife.

“We have an obligation. We have a mission. We have a mandate. The blood of hundreds of innocent men and women is calling out to us.”

- Rep. John Lewis

Stay informed

To get updates, including notification of newly released cases, please join our email list.

Sign up